HAMILTON COUNTY COURTHOUSES

by Steven McQuillin

Fire has played an important role in the history of the courthouses in Hamilton County. Three of the county's six courthouses were destroyed by fire, a record unsurpassed by any other Ohio county. Not only were three fine courthouses destroyed, but invaluable county records and legal documents were also consumed.

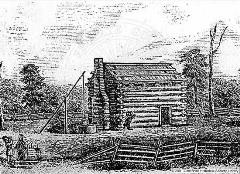

Hamilton County's first courthouse was a log cabin erected in 1790. It stood on what is now Government Square, but which was in the late eighteenth century dotted with swamps and frog ponds. The building was constructed by volunteers and thus cost the county nothing. Measuring fifty feet by forty feet, this was a small building. Because of the lack of facilities for incarcerating offenders, the public whipping post was resorted to as the method of punishment. The whipping post was prominently located directly in front of the courthouse and presumably served as a source of entertainment to the frontier community, which had the opportunity to witness the public administration of justice.

The first courthouse was soon replaced by a more substantial building, reflecting the growing prosperity of what was rapidly becoming Ohio's most important trading center. This 1802 courthouse was located on the public square near the southeast corner of Fifth and Main streets. Constructed at a cost of $3,000 this was a two-story limestone building measured 42 feet across the front and had a depth of 55 feet. The exterior walls of this building rose up above the roofline to form a parapet. Rising from the center of this early courthouse was an arcaded cupola surrounded by a projecting balustrade and surmounted by a wooden dome. This courthouse was used as a barracks during the War of 1812, and through careless soldiers, it was destroyed by fire during this occupancy.

The first courthouse was soon replaced by a more substantial building, reflecting the growing prosperity of what was rapidly becoming Ohio's most important trading center. This 1802 courthouse was located on the public square near the southeast corner of Fifth and Main streets. Constructed at a cost of $3,000 this was a two-story limestone building measured 42 feet across the front and had a depth of 55 feet. The exterior walls of this building rose up above the roofline to form a parapet. Rising from the center of this early courthouse was an arcaded cupola surrounded by a projecting balustrade and surmounted by a wooden dome. This courthouse was used as a barracks during the War of 1812, and through careless soldiers, it was destroyed by fire during this occupancy.

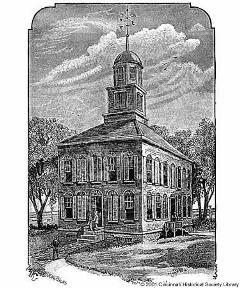

The county commissioners accepted a lot offered by Jesse Hunt, grandfather of noted attorney Elliot Hunt Pendleton as the site for the new courthouse. Located at Court and Main streets, this building was considerably removed from what was then the village of Cincinnati. Built at a cost of $15,000, this third courthouse was not completed until 1819. It resembled the second courthouse in appearance and was an example of Federal style architecture. Drake and Mansfield's book, Cincinnati in 1826, had the following negative comments about this old courthouse:

It presents neither in its domestic economy nor external architecture a model of convenience or elegance. Its removal from the centre of the city is justly a cause for complaint.

It presents neither in its domestic economy nor external architecture a model of convenience or elegance. Its removal from the centre of the city is justly a cause for complaint.

They need not have been so concerned, because the rapidly growing city soon encompassed the courthouse. As to its appearance and utility, fire would settle that question. The building was still in use by 1849, but had been supplemented by wings to house the growing number of offices in Ohio's largest county. The following account of the building's demise was recorded in 1881 by a citizen who was present at the time:

In the afternoon of Monday, July 9, 1849, this old and noble structure burned up, or down, and nothing was left of it but its thick, blackened walls, and they have been made and builded to last forever. The fire had been communicated to it by a neighboring pork-house conflagration on a warm summer's day. It caught on its exposed timber roof and cupola, and soon roof, dome, cupola, spire and steeple were enveloped in flames. I remember gazing intently into the surrounding, wrapping, warping, writhing, enclosing flames atop the immense roof. Dome, spire and steeple and roof soon fell with a tremendous roar into the midst of the enclosing walls, which had been blackened but not injured in their structure by the fire. They stood for a long while a sort of ruined monument of former justice and law . . . During the burning of the roof and dome and tower of the old courthouse it was a very curious and interesting sight to see numerous doves or pigeons flying in extended circles about the flames, as near as the fierce heat would permit them. The cupola had been a long-time home for the pigeons of the city. The old courthouse, it seems, was the home of pigeons as well as the judges and lawyers. It was a great old courthouse and had a great history in its eventful days. Sorry to part with it.

After the fire, the courts and county offices found a temporary home in a pork packing house at the northwest corner of Court Street and St. Clair alley. This was one of numerous such facilities for the slaughter and dressing of hogs in the city, which by that time had acquired the nickname ''Porkopolis''. This temporary courthouse was a large four-story brick building, evidently not occupied at the time for its intended purpose, but which later became the home of Wilson, Eggleston & Company, a large pork packing company. Several offices were housed across the alley from what was for three years to serve as the courthouse.

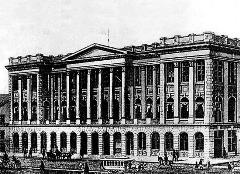

Isaiah Rogers, a prominent architect of national reputation, was selected to design the new courthouse. Rogers was perhaps the country's foremost hotel architect and had recently designed the Burnett House in Cincinnati, the largest and most elegant hotel in the Midwest.

His design for the fourth Hamilton County Courthouse was for a massive three-story building, measuring 190 feet square. Its immense size entirely filled the site at Court and Main streets. The building bore a close resemblance to Rogers' Merchants Exchange building in New York City. Located on Wall Street, this building still stands, with later additions, as the headquarters of National City Bank. A series of arcades accented the ground floor, which was at grade level. The three center bays led directly into the building. Rising above the podium formed by the first floor was a temple-like Greek Revival style building. Its center section was recessed to form a balustraded portico, which was accented by six colossal Corinthian columns supporting a massive triangular pediment in the center of the facade. It rose to a height of sixty feet and was crowned by a massive cornice and balustrade. The front of the building was finished in locally quarried limestone, known as Dayton Marble, while the sides were finished in red brick accented by stone trim.

His design for the fourth Hamilton County Courthouse was for a massive three-story building, measuring 190 feet square. Its immense size entirely filled the site at Court and Main streets. The building bore a close resemblance to Rogers' Merchants Exchange building in New York City. Located on Wall Street, this building still stands, with later additions, as the headquarters of National City Bank. A series of arcades accented the ground floor, which was at grade level. The three center bays led directly into the building. Rising above the podium formed by the first floor was a temple-like Greek Revival style building. Its center section was recessed to form a balustraded portico, which was accented by six colossal Corinthian columns supporting a massive triangular pediment in the center of the facade. It rose to a height of sixty feet and was crowned by a massive cornice and balustrade. The front of the building was finished in locally quarried limestone, known as Dayton Marble, while the sides were finished in red brick accented by stone trim.

The main entrance through the center three bays led to a broad flight of iron steps to the second or main floor to a broad central rotunda room, which was lighted by a massive skylight. This room served as the main criminal court room. Circling the main courtroom was a broad hallway, which led to numerous offices. On the third floor were other courtrooms and the law library and offices. The building was very substantially built of fireproof materials and was well lighted from numerous large windows and the central glass dome, which was invisible from the street. The cost of what for many years was the largest courthouse in Ohio was a then-staggering sum of $695,000 – a sum unequalled by many twentieth century Ohio courthouses.

Work on the third courthouse suffered many frequent delays caused by changes in the plans and conflicting ideas about its style and layout. When the first offices moved into the still-unfinished building in 1852, ''they were small, dark, and cold (offices); and the judges and the bar had a generally unpleasant time of it there. Finally, one of the judges had a long siege with sore eyes, as a result of his attendance in these rooms, and, by arrangement with the supreme court and the three common pleas judges, he secured a peremptory order to the sheriff that other quarters for the courts should be obtained.'' (Following from the 1881 History of Hamilton County, Page 235).

Immediately behind the courthouse was the county jail, which faced onto Sycamore Street. The jail was built of limestone, like the courthouse, and was completed in 1862 in a style to match the courthouse at a cost of $226,500. The building contained 152 cells and was of fireproof construction and surrounded by a high stone wall. A passageway led from the courthouse to this jail building.

Cincinnati's beautiful courthouse, constructed to last for centuries, succumbed after only thirty years of service. Its tragic demise is recounted in this article taken from Henry Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio:

"Cincinnati has never witnessed such violation of the law, defiance of authorities, and so much bloodshed as attended the great Hamilton County Courthouse riot on the night of March 28, 1884, and continuing for several days, there being open conflict between the militia and police on one side and an excitable, yet determined mob upon the other.

The circumstances that led to this most unfortunate affair was the trial for murder of Wm. Berner, who killed his employer, Wm. Kirk.

It was one of the most outrageous assaults upon society, and a dastardly, cold-blooded crime that unsteadied the nerves of the populace, causing excitement to run high, and incensed all law- abiding citizens when the case came to trial by the methods pursued by criminal lawyers, who sought to perjure witnesses, bribe juries, and resorted to openhanded means to have their client acquitted against all principle of law or justice. There was called at the great Music Hall on the evening of March 28, 1884, a mass meeting of citizens. Immediately after the meeting, as the masses were surging out upon Elm street, some one in the crowd shouted, ''Fall in! Let's go to the jail!'' and a great mob from the meeting proceeded directly to the county jail in the court-house on the Sycamore Street side, above Court Street.

On the way the mob was increased by hundreds of others. Upon reaching the jail it was surrounded by a howling, angry crowd. A piece of joist was procured, and with it the basement doors, at the foot of the stone steps, were battered down. Bricks and stone were hurled by men in the street above at the windows. Clubs, huge pieces of timber, crowbars, and other weapons were quickly procured and passed down to the men who were at work upon the heavy outside entrance doors of the jail, and it at last yielded, the work being done speedily. The crowd then poured into the jail office, and there found other obstructions in the matter of stone walls and heavy iron grated doors. Morton L. Hawkins, the county sheriff, and his few deputies faced the mob upon their entrance between the outer and inside doors. They were powerless to stem the fierce human tide, and besides the sheriff had given orders to his officers not to use their weapons on the mob, believing that such proceeding would only make bad worse. The mob completely filled the interior of the jail, yelling and searching for the murderer they had come to hang. They filled the corridors, and a force of men succeeded in so forcing the iron grated door that it at last gave way, and the mob ran up the winding stone stairway to the cell rooms, peering into each cell and demanding of other prisoners the where-abouts of the murderer whom they sought.

While this was going on within a squad of fifteen policemen arrived on the scene and began clearing the jail, meeting with but little success, as they were set upon by the mob and hurled to one side as though they were not there. At 9.55 P.M. the fire-bells sounded the riot alarm. This brought people to the scene from all sections of the city, and they turned in with the mob, the greater majority being in sympathy. It called the police from their posts of duty and the various stations; and through good management they were formed above and below the jail in two sections, and, headed by the patrol wagons, advanced upon the crowds assembled on Sycamore Street, in proximity to the jail. The crowd outside was estimated to be between nine and ten thousand. The patrol and police advancing in two solid columns caused a stampede, the rioters escaping through side streets. Ringleaders and some of those who had been active inside the jail were taken in the patrol wagons to the station houses. The patrols were permitted to leave amid much jeering and denunciatory language, and after their passage the gap was closed up and another onslaught made upon the jail; the rioters in the meantime having armed themselves with axes, stones and bricks.

Upon their being repulsed, however, a great crowd rushed over toward Main Street and down town. Simultaneous attacks were made upon the entrances of several gun stores, and the places completely gutted of firearms, powder, cartridges and other ammunition. In the meantime others of the mob had fired the jail and the courthouse, in a score of places, coal oil and powder being liberally used, and neighboring stores and groceries being sacked for the purpose. Affairs were assuming a serious and critical aspect. The light of the fires illuminated the whole city, causing hundreds of other citizens, upon the hilltops and in the suburbs, to hasten to the scene.

Immediately after the sentence had been pronounced that afternoon the murderer Berner had been hurried to Columbus, going in a buggy to Linwood, where the train was taken. He was in custody of Dominick Devots, a watchman or deputy sheriff, and through the latter's negligence the prisoner managed to escape from him while the train was at Loveland. All these things the rioters of course were ignorant of. They had been told by Sheriff Hawkins that the prisoner was not in jail upon the first attack, but this was looked upon as a subterfuge to cause them to cease their violence. The fires around the jail and court-house had been put out, and towards early morning the mob, almost worn out with their labors, thinned out, but hundreds remained about the scene throughout the night, and as the hours approached the working hour their numbers were increased.

All day long Saturday the militia and police were on duty, and the courthouse and jail were surrounded by tired-out but determined men, and thousands of others drawn there by the excitement of the occasion.

There were no attempts at attack made during the day, but Saturday night for several blocks above and below to the east and the west of the jail and court-house the streets were choked by rioters who had greatly increased their strength, and another attack on the jail was made.

This proved to be the most serious attack of all, and the most disastrous. Admission was gained to the courthouse. The militia in the streets were held in a hollow square formed under the masterful leadership of some of their number. Once inside the courthouse, the work of demolition began. The whole magnificent stone building seemed to become ignited at once. The whole place was gutted and the valuable records of three-quarters of a century's accumulation were destroyed.

The building burned to the ground. The governor of the State had called out the militia of the State, and they were arriving by every train. Their appearance upon the scene seemed to more aggravate and incense the mob, and being fired upon a bloody riot began in the streets, men being mowed down like grass under the keen sweep of a scythe.

Captain John J. Desmond, of the militia, was shot and killed inside the burning courthouse, while leading an attack on the mob. Many prominent citizens received wounds from stray shots of the militia. Windows, doors and even walls of houses in the vicinity of the riot to this day bear evidence of that time of terror and bloodshed.

United States Secretary of War Lincoln ordered to the scene the United States troops, and their appearance seemed to have the desired effect, as the rioters gradually dispersed. The result was, however, that 45 persons were killed and 125 wounded.

Berner, the cause of all this terrible loss and destruction to life and property, was recaptured late on Saturday afternoon in an out-of-the-way house in the woods on a hillside near Loveland. When captured by Cincinnati detectives, aided by the marshal of Loveland, he was coolly enjoying a game of cards, and was unaware of the riot and the attack upon the jail. He was taken to Columbus and lodged in the State penitentiary under the sentence that had been passed upon him on the 26th day of March of confinement for twenty years."

Among the many persons killed in this incident was the militia commander, John J. Desmond, whose statue stands in the current courthouse lobby. Destroyed in the fire were records of Hamilton County, dating back nearly I 00 years. The law library, considered to be the finest in the country, was also destroyed. All that remained of Isaiah Rogers courthouse, frequently referred to as the ''finest public building in the West'' were its immense stone walls. The state legislature passed a bill creating a board of trustees to oversee the reconstruction of the courthouse. Governor George Hoadley appointed as trustees Henry C. Urner, John L. Stettinius, Wesley M. Cameron and William Worthington. This board of trustees served without compensation for 2 ½ years until the fifth courthouse was formally dedicated. On January 15, 1887, the Bar Association gave a banquet for the trustees and their architect, James W. McLaughlin, as a tribute for their work in rebuilding the courthouse.

Among the many persons killed in this incident was the militia commander, John J. Desmond, whose statue stands in the current courthouse lobby. Destroyed in the fire were records of Hamilton County, dating back nearly I 00 years. The law library, considered to be the finest in the country, was also destroyed. All that remained of Isaiah Rogers courthouse, frequently referred to as the ''finest public building in the West'' were its immense stone walls. The state legislature passed a bill creating a board of trustees to oversee the reconstruction of the courthouse. Governor George Hoadley appointed as trustees Henry C. Urner, John L. Stettinius, Wesley M. Cameron and William Worthington. This board of trustees served without compensation for 2 ½ years until the fifth courthouse was formally dedicated. On January 15, 1887, the Bar Association gave a banquet for the trustees and their architect, James W. McLaughlin, as a tribute for their work in rebuilding the courthouse.

McLaughlin's design consisted primarily of reconstructing the interior partitions apparently in much the same fashion and refacing the old courthouse with a new front. The new stone front was executed in the then fashionable Richardsonian Romanesque style. The side walls of Rogers' courthouse were left intact and the new front was made to conform basically to Rogers' plan, but in the new style. The central portico was omitted in the rebuilding and another floor was added to the top of the central portion. The result was a curious blending of classical and romantic forms, similar to what can be observed today on a much smaller scale in the Pickaway County Courthouse. It is likely that McLaughlin's early use of the Romanesque style was to exert a heavy influence on later public buildings, such as the Chamber of Commerce Building, which has been destroyed, and the city hall by Samuel Hannaford, which still stands.

McLaughlin's design consisted primarily of reconstructing the interior partitions apparently in much the same fashion and refacing the old courthouse with a new front. The new stone front was executed in the then fashionable Richardsonian Romanesque style. The side walls of Rogers' courthouse were left intact and the new front was made to conform basically to Rogers' plan, but in the new style. The central portico was omitted in the rebuilding and another floor was added to the top of the central portion. The result was a curious blending of classical and romantic forms, similar to what can be observed today on a much smaller scale in the Pickaway County Courthouse. It is likely that McLaughlin's early use of the Romanesque style was to exert a heavy influence on later public buildings, such as the Chamber of Commerce Building, which has been destroyed, and the city hall by Samuel Hannaford, which still stands.

It is not surprising that the fifth courthouse, which was essentially the same size as the 1853 building, would soon be outgrown by the county government. Yet it is remarkable that less than thirty years after its completion the courthouse was demolished. Few public buildings from this era have had so brief an existence.

It is not surprising that the fifth courthouse, which was essentially the same size as the 1853 building, would soon be outgrown by the county government. Yet it is remarkable that less than thirty years after its completion the courthouse was demolished. Few public buildings from this era have had so brief an existence.

Agitation had been developing for the construction of a new jail to replace the county jail directly behind the courthouse. Civic organizations and individuals found that the building was not only obsolete and inadequate, but it was also damp and unhealthy. On October 2, 1908, the County Commissioners passed a resolution providing for the construction of a new jail and for levying a tax to support a bond issue for that purpose. The measure was approved by the voters and a planning committee was appointed to oversee its implementation. The committee ultimately recommended that not only should the jail be replaced but that a new courthouse be constructed at the same time, or at the least, an enlargement of the current facility.

At this time, Cleveland was well on its way to planning a comprehensive civic center in its downtown with a new county courthouse as a major focal point. This same desire to create a downtown civic center took form in Cincinnati when the canal at the northern edge of the downtown was abandoned. A broad avenue was planned for its site and is now known as Central Parkway. It was decided to have the new jail and courthouse conform to the concepts then being proposed for the Canal Parkway. On September 26, 1911, the County Commissioners prepared a resolution calling for the issuance of bonds totaling $2,500,000 for a new courthouse and jail. The issue was approved by the voters and on April 1, 1915 the contract for the work was let to the Charles McCaul Co., and work began that same day. During the period form 1915 to 1919, county offices occupied temporary quarters in the Fleischer Building, presumably a better arrangement than that secured in 1849. The new courthouse, whose construction continued with some difficulty during the First World War, was completed and formally dedicated in October 1919. The total cost of the building and its furnishings was $3,022,000.

The exterior of the sixth and present courthouse is Renaissance Revival in style and is constructed with New Hampshire granite and Bedford limestone. Like the 1853 courthouse, this building is elevated on a one story base set at grade level. Above this ground story arc three main levels grouped together by a colossal row of Corinthian columns. Like the earlier courthouse, this building consumes much of its site, with little room left for lawn or open space. Its location on a broad parkway makes the courthouse highly visible. The building is entered through three wide arched doorways on Main Street which feature finely wrought bronzed screens. Flanking the doorways on each side are arched windows of the same character.

The exterior of the sixth and present courthouse is Renaissance Revival in style and is constructed with New Hampshire granite and Bedford limestone. Like the 1853 courthouse, this building is elevated on a one story base set at grade level. Above this ground story arc three main levels grouped together by a colossal row of Corinthian columns. Like the earlier courthouse, this building consumes much of its site, with little room left for lawn or open space. Its location on a broad parkway makes the courthouse highly visible. The building is entered through three wide arched doorways on Main Street which feature finely wrought bronzed screens. Flanking the doorways on each side are arched windows of the same character.

The law library was regarded as the showroom of the entire building. As the Cincinnati Law Library was considered to be the most complete law library in America, no expense was spared to provide it with fitting quarters in the new building, including many unusual features and building materials from all over the country.

This beautiful building has served Hamilton County for over ninety years without serious mishap, setting a record of longevity, the average length of service for its predecessors being well under thirty years. The building survives in good condition with its major architectural features intact.

| Hamilton County Courthouses | |

|---|---|

| 1790, Cincinnati | |

| 1802, Cincinnati (picture not available) | |

| 1819. Cincinnati | |

| 1854, Cincinnati. Isaiah Rogers, architect | |

| 1887, Cincinnati | |

| 1919, Cincinnati | |

>

>